Existential coaching is a coaching approach with depth that focuses on the big questions of life: death, uncertainty, anxiety and meaning.

In my last post, I wrote about my growing interest in existential coaching, an approach to coaching I wasn’t familiar with but which had picked up my curiosity. I have researched it and now know a bit more about it, so I’d like to share with you what I learned.

Existential Coaching is based on Existential Philosophy

“If he comes to you asking for advice, he has already chosen a course of action. In practical terms, I could very well have given him advice. But since his goal was freedom, I wanted him to be free to decide.”

Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism

A student asked Sartre for advice on his dilemma: should he go to war to avenge his brother’s death or stay with his mother? As any good existential coach would have done in his place, Sartre decided not to give him the advice he sought and to let him exercise his freedom.

Sartre was an existential philosopher, playwright, writer, political activist and many other things, but not a coach, not even an existential one. Apart from sports coaching, other types of coaching did not become widely used until the 80s, while the existential sort did not get traction until the 2000s, well past Sartre’s death in 1980.

Sartre was not an existential coach but had, together with other philosophers like Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Husserl, or Nietzsche, or writers like Camus or Dostoevsky, an immense influence on existential coaching, as this is based, like existential therapy before it, on the principles of existentialism.

Existential coaching has a philosophical foundation but with a pragmatic approach: to help clients live more deliberate and freer lives.

Existential coaches believe in the freedom of individuals to forge their lives, so no single methodology works for all. There is not a unified framework applicable to all existential coaches. Like their philosophical forefathers, they are diverse and unique, but they do share their focus on particular themes: relatedness, uncertainty, anxiety (especially of the existential sort), death and temporality, meaning and meaninglessness, absurdity, freedom, choice and authenticity.

These are universal themes. You don’t need to be an existentialist to ponder about them. I wrote about death, temporality, or the meaning of life a while back already, and that doesn’t make me an existentialist, far from it.

The work of the existential coach

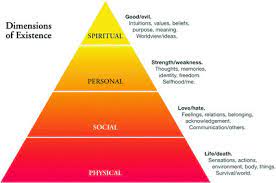

An existential coach will explore these themes and the client’s values in the four dimensions of existence defined by Heidegger: the physical (umwelt), the social (mitwelt), the personal (eigenwelt) and the spiritual (uberwelt). By covering all these dimensions, they make sure they review the client’s worldview from a broad perspective, and they don’t miss anything during this exploration.

Like in other humanistic coaching approaches, existential coaches believe that their clients have the necessary resources within themselves and the self-actualisation tendencies to find the best solutions for them so that they will put the client at the centre of the session, but they will instil a clearer direction than, for example, person-centred coaches (in person-centred coaching, the coach mainly reflects what she hears to the client, doesn’t guide through questions), by framing the conversation within the existential themes mentioned above and the four existential dimensions.

“The most common form of despair is not being who you are.”

Soren Kierkegaard

Not being who you are, not being authentic, is one of the biggest sins for existentialists. Existential coaches help clients understand who they are and what gives meaning to their lives. They believe life is meaningless and absurd, except for the meaning we decide to give it. There is no meaning of life, but we can find meaning in life.

Existential coaches explore these and other profound themes like death, freedom, anxiety, uncertainty and relatedness. It is an approach with depth, where clients are pushed to look into their inner worlds and grapple with paradoxes. This depth is arguably its biggest strength.

Existential coaching may not be the best approach for learning specific skills, but it is one of the most profound coaching approaches, best suited for clients to gain self-knowledge and find meaning, manage life transitions or face major life decisions.

Existence precedes essence, but does it?

“Existence precedes essence”.

Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism

Sartre thought that this was the first principle of existentialism. It means that human beings build their essence through their decisions and choices. They exist before they can conceive who they are. They are free to develop their essence. This is why freedom is one of the main themes of existentialism.

We are all free to do whatever we want as long as we assume the consequences. You are free to leave that job you don’t like or your partner for twenty years, as long as you are OK with being jobless or single. We are not forced to do anything; we set our own limits. Freedom brings with it responsibility. That’s why Sartre famously said that we are all “condemned to be free”.

This is the most liberating aspect of existentialism, which, despite its gloomy and dark fame, is an optimistic and empowering philosophy.

However, if “existence precedes essence” is the foundation of the entire existential edifice, it was built on shaky biological, psychological, and philosophical grounds.

Biologists and psychologists are still figuring out how much of our personality is due to our genetic makeup or life experiences, but they seem to agree that both nature and nurture play a part, which means that at least part of our “essence” is inherited, not defined by us. Attachment theory states that another important part is developed in the early years of life when we are too young to have a real choice about it.

Also, it is unclear whether free will exists. If we are not free to choose, how can we create our essence through our actions? How can we be “condemned to be free”?

We could argue that it does not matter whether a coaching client is really free to define who they are. As long as they believe they are free, they might find existential coaching helpful.

No goals, no solutions?

Unlike many other coaching approaches, existential coaching is not a solution or goal-focused approach. There is a phenomenological enquiry of the client’s worldview, values and the existential themes and paradoxes preoccupying them, so it lacks the structure and goal orientation of most other approaches.

That doesn’t mean that there are no solutions or goals achieved. All clients come to a coaching assignment with a problem, aspiration or aim, even if not explicitly stated. They want to achieve something; otherwise, they wouldn’t go through the coaching process.

In existential coaching, they may not state clearly their goals, and the coach and the client wouldn’t spend the time they would spend on other approaches to define well the goals of the assignment. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t work or it doesn’t help clients find solutions to their problems and live more fulfilling lives.

Existential coaching is a relatively recent approach, and little research has been carried out about its effectiveness as a coaching practice, but it does seem to work in certain situations and for certain types of clients.

As mentioned, it won’t necessarily work on coaching processes focused on building specific skills, but it can be very effective in transformational or developmental coaching. It can help clients know themselves better, find meaning in their lives, manage the existential anxiety we all seem to live with and live happier lives.

Despite its purely Western origins (mainly from European men), existentialism aims to deal with universal themes. We all think about our death and temporality in this life, what it means to be free or authentic. In that sense, existential coaching can help us all better grapple with these issues and live lives that are aligned with our purpose and values.

I have started practising it with some of my clients, with their consent. Existentialism is not for everybody, but it works well with some people, especially with the most philosophically minded or reflective ones.

I will continue learning more about it and practising it. After all, we all think about existential themes once in a while, and I am no exception. Knowing more about it will allow me to be a better coach, but more importantly, to deal better with my own existential issues.